9 - Integrated Pest Management

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is a common-sense approach to managing pests. The objective is to give priority to the least toxic pesticide when applications are necessary. This helps reduce risk of pesticide exposure to people, animals, and the environment. It also helps with managing expenses and conserving energy.

Golf course superintendents must understand what IPM is and how to implement it for each pest group, including insects, diseases, weeds, and nematodes. It is important to have a thorough knowledge of types of pests, lifecycles and/or conditions that favor pests, ways to prevent pests, and methods of pest control. IPM benefits can include less pesticide use, less disruption of natural biological control, reduced risk to human health, improved efficiencies and cost-effectiveness.

IPM aims to reduce conventional pesticide use, when feasible, by using an integration of multiple tactics to control pests, including cultural or mechanical, biological, genetic, and chemical controls.

Best Management Practices

Always adhere to local, state, and federal regulations for pesticide application, restricted use pesticides (RUP), and biological controls

Proper records of all pesticide applications should be kept according to local, state, or federal requirements

Collect soil samples annually to assess soil fertility and pH; proper soil pH and fertility help prevent diseases and promote plant health to reduce potential for insect and weed invasion

Establish a written IPM plan. Monitor, observe, and document turf conditions regularly (daily, weekly, or monthly, depending on the pest), scout which pests are present, level of damage, determine pest thresholds, and necessary control strategies

Scout to identify key pests on key plants; determine pest’s lifecycle, know which life stage to target (e.g., for an insect, whether egg, larva/nymph, pupa, or adult)

Decide which pest management practice (mechanical, chemical, biological) is appropriate and carry out corrective actions

Use proper cultural, mechanical, or physical methods to prevent problems (e.g., prepare site, choose correct turfgrass for Connecticut; select resistant cultivars), reduce pest habitat, practice good sanitation, pruning, dethatching

Consider biological controls that support natural predators and beneficial organisms to reduce pests

Mow when grass is dry to avoid spread of turf diseases; maintain sharp cutting edges to avoid stress; properly manage grass clippings (reference Cultural Practices BMP Section)

Chemical pesticide applications should be carefully chosen for effective, site-specific pest control; use properly timed preventive chemical applications only when professional judgment indicates they are likely to control the target pest effectively, with minimal environmental and economic impact

Rotate chemicals and modes of action to reduce resistance in pests; always follow label instructions

Train employees on pest identification, pesticide selection, application techniques; entomologists and other specialists are available from the University of Connecticut - UConn Plant Diagnostics Laboratory https://plant.lab.uconn.edu/, Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) https://portal.ct.gov/DEEP/Pesticides/Integrated-Pest-Management/Integrated-Pest-Management, and Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES) https://portal.ct.gov/CAES/ABOUT-CAES/How-To-Contact/How-to-Contact-The-Station other extension agencies for assistance with pest identification

Determine whether corrective actions reduced or prevented pest populations; were economical and minimized risks; record and use information when making future decisions

Maintain a supply of PPE for use when working on pesticide application equipment.

IPM Plan & Monitoring

IPM on golf courses focuses on identifying pests, choosing pest-resistant varieties of grasses and other plants, enhancing habitat for natural pest predators, scouting to determine pest populations and acceptable thresholds, and applying biological and other potentially less-toxic alternatives whenever possible. Chemical controls should minimize impacts on the environment and potential for development of pesticide resistance.

Written Plan

A written IPM plan should be established to provide guidance and align crew members. IPM includes biological controls, cultural methods, chemical controls, pest monitoring, and other applicable practices. The written plan should establish responsibilities, pest action thresholds, a system of communication, and pesticide-use hierarchy. A pest-control strategy should only be used when the pest is causing, or is expected to cause, more damage than what can be reasonably and economically tolerated. A control strategy should reduce pest numbers to an acceptable level, while minimizing harm to non-targeted organisms and the environment.

Reference a sample IPM Plan for Turf from DEEP at https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/DEEP/pesticides/IPM/IPMOrnamentalandTurfPlanpdf.pdf

Pest Thresholds & Scouting

Include “scouting” of locations and steps for all areas of the course in the IPM written plan. Scout to identify populations, pest damage, determine acceptable thresholds, and what control strategies are needed. Scouting methods include visual inspection, soil sampling, soap flushes, and insect trapping. Keep a record of scouting results for historical information, to document numbers of pests, patterns of pest activity, size of area affected, successes and failures. Use this information when making future decisions. Use Growing Degree Day (GDDs) calculations for assistance in monitoring for pest presence.

Educating golfers and maintenance personnel can raise understanding and tolerance of minor aesthetic damage without compromising plant health, play, and aesthetics. Pest thresholds help guide application decisions and associated education, while minimizing economic and environmental costs. Pest population, lifecycle stage of the pest, and life stage of the plant are several factors considered to determine thresholds.

Reference samples of suggested insect pest thresholds:

DEEP https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/DEEP/pesticides/IPM/IPMOrnamentalandTurfPlanpdf.pdf

University of Connecticut http://cag.uconn.edu/documents/Turfgrass-IPM-manual-s.pdf

Note that some recommended action thresholds may be lower (6 to 10 grubs per square foot) depending upon species. Additional threshold reference for the Annual bluegrass weevil:

https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/42417/ann-bluegrass-weevil-FS-NYSIPM.pdf?sequence=1

http://www.turfgrassdiseasesolutions.com/sys/docs/12/factsheetoriginal.pdf

Monitoring

Monitor, observe, and document the presence and development of pests regularly – this could include daily, weekly, or monthly monitoring, depending on the pests. Note time of day, month, year, weather, and flowering stages of nearby plants to determine conditions which are conducive to outbreaks. Map outbreak locations (including number of insects per unit area, disease patch size, and percent of area affected) to identify patterns and susceptible areas. Problem areas might include the edges of fairways, shady sites, or poorly drained areas. Document with photos when possible; use GGDs.

Personnel should be trained to determine the pest’s lifecycle and know which life stage to target. For example, for an insect pest - identify whether it is an egg, larva/nymph, pupa, or adult. It is important for staff to document, identify, and record key pest activities on key plants. Signs of the pest may include mushrooms, animal damage, insect frass, or webbing. Symptoms of the pest may include chlorosis, dieback, growth reduction, defoliation, mounds, or tunnels. The staff should note which corrective actions reduced or prevented pest populations and they should be trained to understand what actions are most economical, while minimizing risks. Help with diagnostics is available at https://plant.lab.uconn.edu/

Pest Groups

Insects

Insects can be destructive to turfgrass and disruptive to play. It is important to correctly identify the responsible insect pest and pest lifecycle to determine the best course of management. Identification often involves sending samples to diagnostic clinics. Specialists are available from UConn through the Plant Diagnostic Laboratory at PlantDiagnosticLab@uconn.edu to assist with pest identification. Insect pests may damage the plant by surface feeding or root feeding. Turfgrass managers have multiple tactics and tools that can be used to control turf insect pests, including cultural and chemical practices.

Surface feeding insects prosper in thatch. Manage thatch depth through core cultivation, verti-cutting, and topdressing. Root feeding insects include white grub species which are the most destructive insect pest of cool season turfgrasses.

Healthy, well-managed turfgrass is more likely to resist insect problems and has better recuperative potential than stressed, unhealthy turf. Cultural factors that influence stress include organic layer management, fertility programs, water management, and mowing height selection. Correct conditions that produce stressful environments for turf. (e.g., improve airflow and drainage, reduce or eliminate shade, etc.)

The appropriate (most effective) preventive insecticide can be applied to susceptible turfgrasses when unacceptable levels of insect damages are likely to occur. Certain well-studied biological control agents (i.e., entomopathogenic nematodes, fungi, and bacteria) can be used against certain turf insect pests.

Record and map insect outbreaks. Identify trends to help guide future treatments and focus on changing conditions within susceptible areas to reduce insect outbreaks. For a listing of insect pests in Connecticut, visit: https://portal.ct.gov/CAES/Publications/Publications/Listing-of-all-Available-InsectPest-Plant-and-Miscellaneous-Fact-Sheets.

Diseases

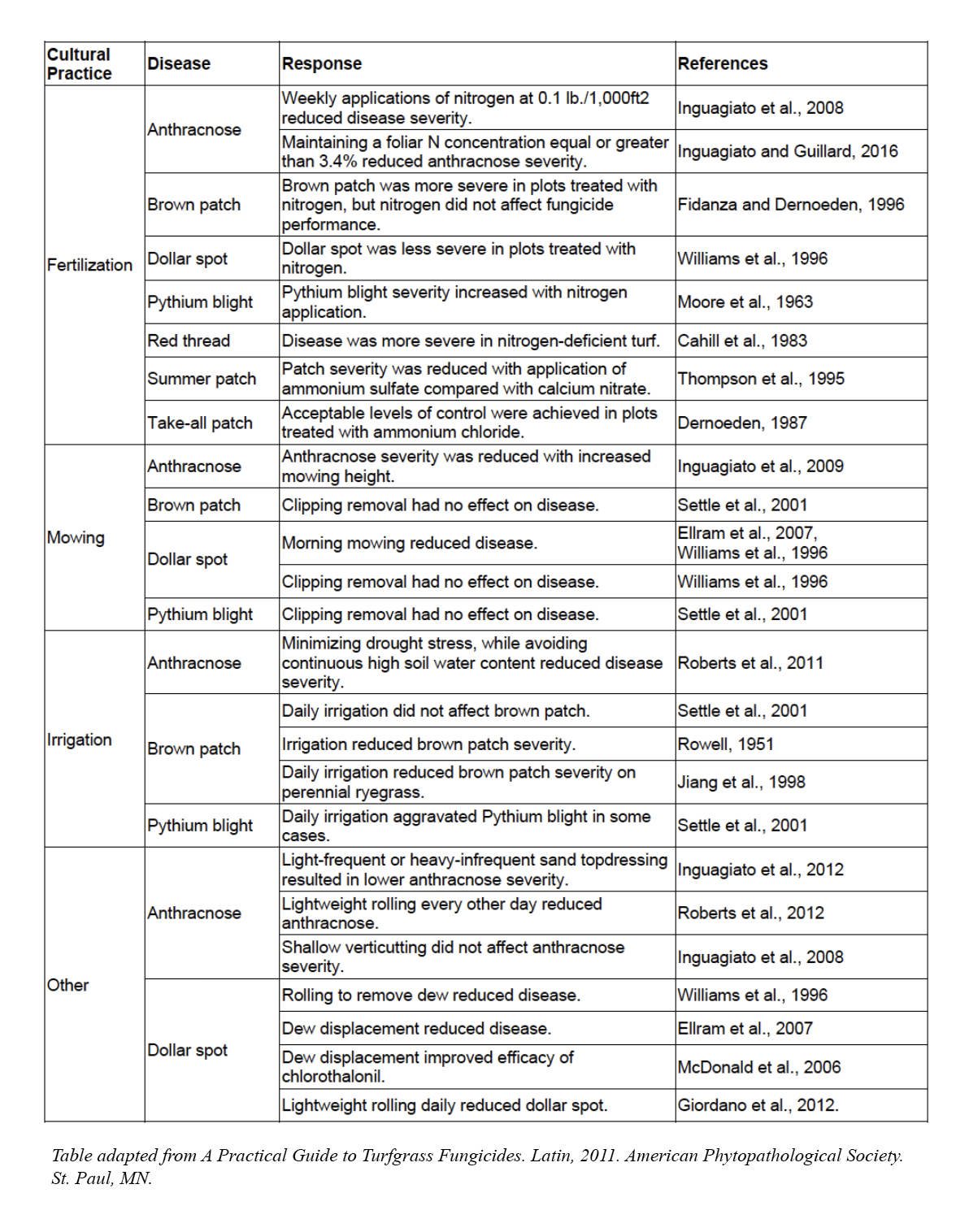

Sound cultural practices are important for maintaining healthy turfgrass to prevent disease outbreaks. Plant pathogens can impact plant health and quality of turf, which in turn affects play. There are three components to consider with disease outbreaks: the host, pathogen, and environment – referred to as the “disease triangle”. Conditions such as excess soil moisture or mowing when turf is wet can influence fungal disease outbreaks. In order to correctly identify the disease pathogen, samples may be sent to diagnostic clinics such as UConn’s Turfgrass Disease Diagnostic Center at https://cahnr.uconn.edu/turflab/

Cultural factors which can reduce the likelihood of disease include organic layer management, fertility programs, water management, and mowing height selection. Proper cultural practices can help correct conditions that produce stressful turf environments (e.g., improve airflow and drainage, and reduce or eliminate shade). Many diseases are caused by moist conditions. A beneficial way to limit the infestation is to irrigate deeper and less frequently, if conditions allow. Healthy, well-managed turfgrass is less likely to develop disease given its better recuperative potential.

Fungicide use should be integrated into an overall management strategy for a golf course. Record and map disease outbreaks identify trends to guide future treatments, and alter conditions in susceptible areas to reduce disease outbreaks. The appropriate (most effective) preventive fungicide can be applied to susceptible turfgrasses when unacceptable levels of disease are likely to occur.

Weeds

Weed infestation can affect the health of turfgrass, negatively impacting plant life and playing surface. People, animals, birds, wind, and water can distribute seeds which reproduce into weeds. Weeds also spread vegetatively - tubers, corms, rhizomes, stolons, creeping stems, or bulbs. Weeds compete with turf for space, water, light, and nutrients. They produce additional problems acting as hosts for plant pathogens, nematodes, and insects; in addition to producing allergic reactions and skin irritants.

The best defense against weeds is proper cultural practices and nutrient management to support healthy turfgrass, integrated with an intelligent herbicide program. A successful weed management program consists of:

Preventing weeds from being introduced into an area

Selecting appropriate turf species or cultivars adapted to prevalent environmental conditions to reduce weed encroachment

Using proper turfgrass and nutrient management in combination with cultural practices to promote vigorous, competitive turf

Properly identifying weeds and understanding lifecycles

Understanding all IPM control measures, properly selecting and using appropriate herbicide, if necessary

Adopt or maintain cultural practices that protect turfgrass from environmental stresses such as shade, drought, and extreme temperatures in order to prevent weed encroachment. Proper turf management practices include correct and appropriate use of fertilizers and chemicals, proper mowing height and frequency, proper soil aeration, and regulated traffic to reduce physical damage and compaction. Proper fertilization helps resist diseases, weeds, and insects; it is essential for turfgrasses to sustain desirable color, growth density, and vigor. Dense, thick turfgrass helps prevent weeds from establishing; avoid scalping, which reduces turf density and increases weed establishment. Use weed-free materials for topdressing. Aggressive overseeding has been shown to reduce weed populations as a reduced-pesticide method.

Record and map weed infestations to help identify site specific issues for preventative actions. Address damage from turfgrass pests such as diseases, insects, nematodes, and animals to prevent density/canopy loss to broadleaf weeds. Invasive weeds in Connecticut include the Japanese knotweed, Purple loosestrife, and Giant Hogweed. For a list of common Connecticut weeds which exist in the presence of adverse site conditions, visit http://cag.uconn.edu/documents/Turfgrass-IPM-manual-s.pdf.

Nematodes

Plant-parasitic nematodes adversely affect turfgrass health. These microscopic roundworms (unsegmented), usually between 0.0156 and 0.125 inch in length, debilitate the root system of susceptible turfgrasses. The roots under nematode attack may be very short, with few root hairs, or appear dark and rotten.

Plant-parasitic nematodes cause turf to be less efficient at water and nutrient uptake and make it more susceptible to environmental stresses. Weakened turf favors pest infestation and weeds. Turfgrasses begin showing signs of nematode injury during stress, drought, high temperatures, low temperatures, and wear.

Recommended practices when nematode activity is suspected:

Assay the soil and turfgrass roots to determine extent of the problem

Only apply nematicide on golf course turf based on assay results

Divert traffic from areas stressed by insects, nematodes, diseases, or weeds

Increase mowing height to reduce plant stress associated with nematodes (in addition to root-feeding insects, disease outbreaks, or peak weed-seed germination)

Reduce or eliminate other biotic/abiotic stresse

Control Methods

Turfgrass Selection & Maintenance

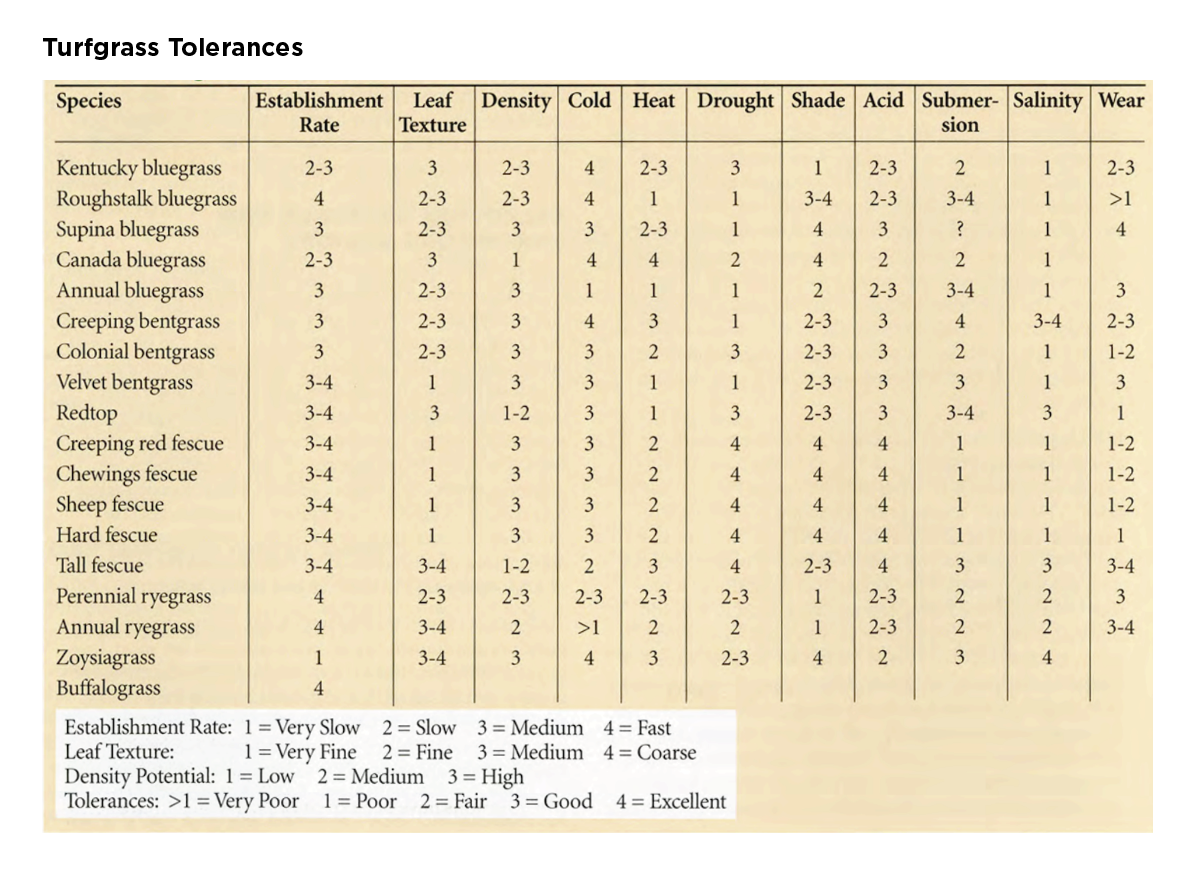

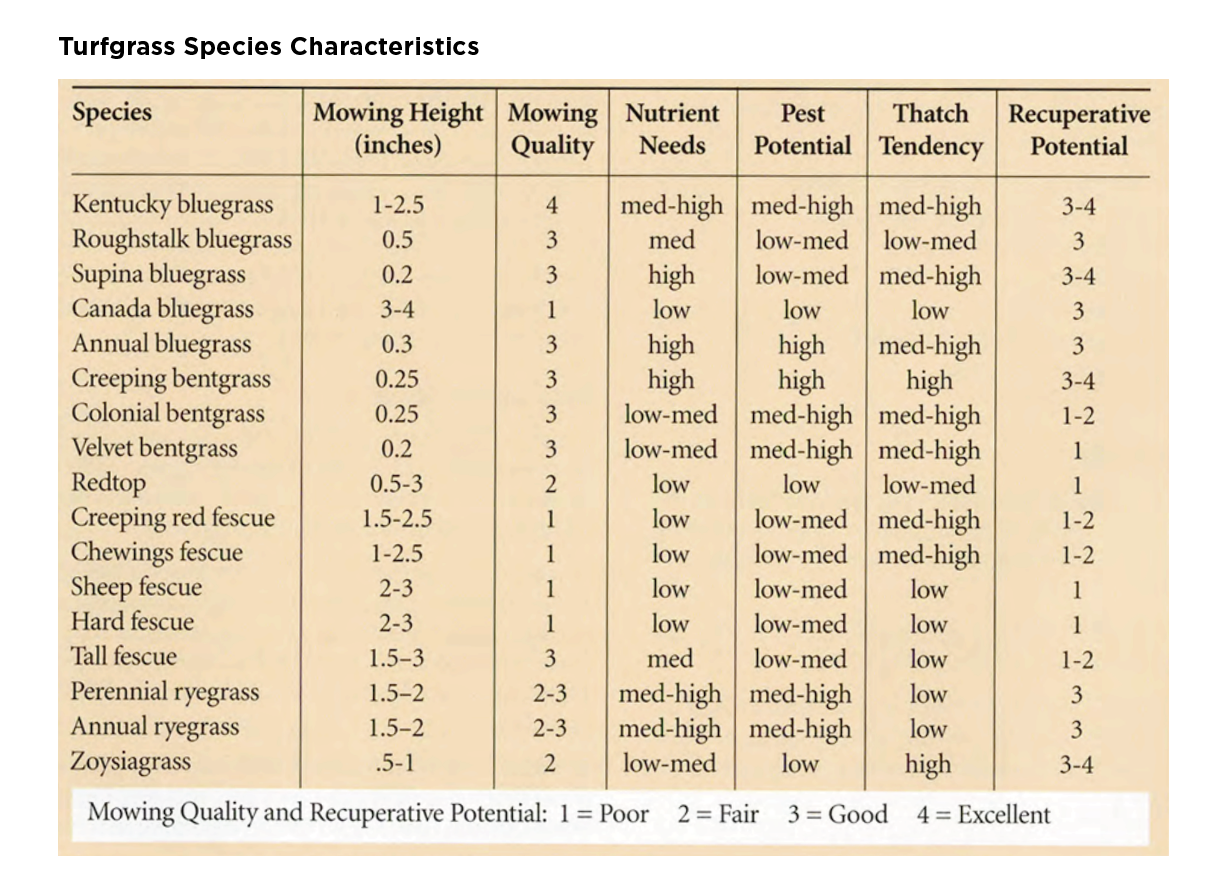

Selecting pest-resistant cultivars or plant species could potentially help reduce pesticide usage. A species grown outside of its zone of adaptation is typically more prone to pest problems. Species and cultivars should be managed under conditions similar to the intended use (e.g., not exceeding mowing height limitations that a grass was bred or selected for). Reference the National Turfgrass Evaluation Program for help with cultivar selection: http://www.ntep.org/

Proper cultural practices are important to reduce plant stress and keep turf healthy. Pests can be minimized through proper irrigation, mowing (height, frequency, pattern), clipping management, topdressing, core aerification, and venting. For example, varying mowing pattern encourages vertical growth, increases tolerance from wear, and minimizes soil compaction. Core aerification reduces compaction, increases infiltration capacity, and encourages root growth – however may produce adverse effects, so should be managed appropriately (i.e. topdressing turf area with suitable soil).

Avoid use of turfgrass in heavily shaded areas and select shade-adapted grasses for areas receiving partial sun or shade. Minimize stress and leaf wetness by correcting dead spots and air-circulation issues by pruning understory and adjusting irrigation scheduling. When pest populations are low, mechanical control methods such as vacuuming, hand pulling weeds, and extracting pests may be used.

Educate builders, developers, golf course and landscape architects, sod producers, and golfers on which plants are best suited to Connecticut. Turfgrasses must be selected which are appropriate within the climate zone and region of the golf course. This helps turfgrass health and tolerances to minimize irrigation requirements, fertilization needs, and pesticide use. For information on turfgrass species, visit http://ntep.org/contents2.shtml.

Reference Planning, Design, and Construction, Irrigation, and Cultural Practices for additional BMPs.

Biological Controls

The biological component of IPM involves the release and/or conservation of biological control agents, such as predators, parasites, and pathogens. Entomologists at the University of Connecticut and the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Valley and New Haven Laboratories can provide informational resources.

https://portal.ct.gov/CAES/ABOUT-CAES/How-To-Contact/How-to-Contact-The-Station

Areas on the golf course can be modified to better support natural predators and beneficial organisms (e.g.; diversifying landscaping with flowering plants to provide sources of pollen and nectar). This natural control can have immediate and long-term impacts including reduced pesticide use, improved native plant growth, lower energy use, water and cost reductions.

Understand the lifecycles of beneficials. When feasible, avoid applying pesticides to roughs, driving ranges, or other low-use areas to provide a refuge for beneficial organisms. Targeted areas for biological controls should attract natural predators and protect them from pesticide applications. Plant insectary plants that provide pollen or nectar sources. Regularly monitor to spot outbreaks and transfer beneficial insects into the area needed.

Nematodes can serve as a biological control organism. There are two nematode families Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae that can be useful for insect pest management, Nematodes infect hosts such as white grubs and billbug larvae by releasing bacteria within the host causing it to die. Nematodes are considered an environmentally friendly pest control option, as they occur naturally without need for genetic modification. It is important to select the appropriate nematode species for the targeted pest. To test a nematode shipment for effectiveness, contact the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Valley Laboratory in Windsor, CT.

Conventional Pesticides

IPM involves prevention and suppression to reduce pest numbers or damage to an acceptable level. A pest-control strategy using pesticides should be used after, or in alignment with, proper cultural practices to control for pests. Pesticides should be used only when the pest is causing, or is expected to cause, more damage than what can be reasonably and economically tolerated.

Pesticides should be evaluated on effectiveness against the pest, mode of action, life stage of the pest, personnel hazards, non-target effects, potential off-site movement, method (spot treatment vs widespread applications), frequency (some low toxicity herbicides may require multiple applications) of application, and cost. An additional evaluation measure which may be considered is the environmental impact quotient (EIQ). The EIQ provides criteria to supplement knowledge of efficacy, cost, and resistance management in helping to determine chemical pesticide options when necessary.

For EIQ information:

http://turf.cals.cornell.edu/pests-and-weeds/environmental-impact-quotient-eiq-explained/

https://nysipm.cornell.edu/eiq/calculator-field-use-eiq/

Pesticides are designed to control or alter behavior of pests - a control strategy should reduce pest numbers to an acceptable level, while minimizing harm to non-targeted organisms. Growing degree days (GDD or DD) are a measure of the “heat units” (related to temperature and the amount of time per day that an insect spends actively growing) that accumulate over time. Monitoring GDD accumulation can help determine when specific insect pests are likely to be present in order to determine best control strategy.

Several available tools and resources may be found at:

http://uspest.org/cgi-bin/ddmodel.us

http://gddtracker.msu.edu/

http://turf.eas.cornell.edu/

Train employees on proper pest identification and pesticide selection techniques. Choose the product most appropriate for the pest and mix only the quantity of pesticide needed in order to avoid disposal problems, protect non-target organisms, and reduce costs. Spot-treat pests whenever appropriate. Rotate pesticide modes-of-action to reduce likelihood of resistance.

For information on rotation and resistance management reference:

https://www.frac.info/fungicide-resistance-management

https://www.hracglobal.com/

https://irac-online.org/

Always follow label instructions; state and federal pesticide laws require it. Note environmental hazards and groundwater advisories included on labels. Follow guidelines provided by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee, Herbicide Resistance Action Committee, and Insecticide Resistance Action Committee. DEEP may be contacted for more information about IPM or other pesticide concerns.

Record-Keeping

Record pesticide applications, along with results of scouting, to develop historical information, document patterns of pest activity, and note successes and failures. Record-keeping is required to comply with the federal Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA, Title III). Certain pesticides are also classified as RUP, refer to https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/DEEP/pesticides/restrictedpermitusepesticidespdf.pdf.

Record-keeping and supervisory written instruction requirements apply per Connecticut General Statutes and Regulations. Supervisory written instructions are required to be maintained as part of the permanent pesticide application record. Records must be maintained for 5 years. Refer to: https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/DEEP/pesticides/Certification/Supervisor/Statsandregspdf.pdf

There are several resources available to assist with record-keeping, examples include:

Playbooks for Golf https://goplaybooks.com/coverage.html

Sparks https://sparks2.com/

PeRK https://cropwatch.unl.edu/unl-releases-perk-20-pesticide-recordkeeping-app